My research interests and projects broadly include young stars and planets, in particular:

- Leveraging Gaia to understand young stellar populations and their star forming history. (See my paper about the Taurus star forming region here)

- Young stellar activity, including as a probe of stellar astrophysics and its effect on RV observations. (See my paper about the NIR Helium triplet’s activity here and a conference talk about the work here)

- The architecture of young planetary systems and their formation pathways

- Spectroscopic data reduction and analysis

Below I talk in more detail about some of the main projects I have worked on.

The Taurus star forming region’s substructure and history

Gaia has provided an unprecedented level of high quality astrometry and photometry across the entire sky. With its high precision, we can use Gaia data to map the 3D (and including radial velocities 6D) structure of stellar populations which can back out a picture of how they formed and constrain the theories of star formation, such as the role of different triggers of star formation or the dispersal mechanisms of stellar groups.

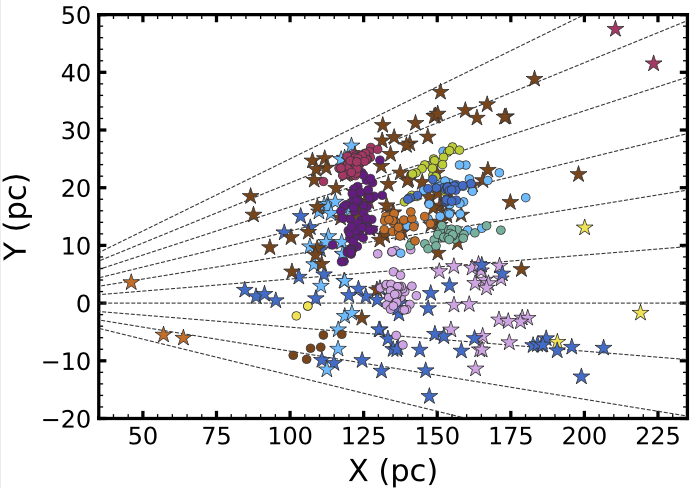

In work I presented as the first chapter in my dissertation, I compiled the most comprehensive census of the Taurus star forming region’s stellar population to date, and used Gaia to map its structure and uncover its star forming history. Taurus is the canonical region of low mass star formation, but it has a complex history with multiple populations that are still not yet fully understood. In this work, we found significant spatial substructure in Taurus’s stellar population, with two types of subgroups: those tightly confined in space (and preferentially near the clouds) and those that are distributed throughout the region. Check out a cool interactive plot here showing the Taurus stellar population and our identified subgroups in galactic 3D space. The plot to the right shows the Taurus stellar population in the galactic XY plane, with different markers indicating different stellar groups.

The region as a whole is fairly coherent in kinematics, although there are some hints of kinematic substructure that correlate with spatial position. On average, the tightly confined groups are younger than the distributed groups, which makes sense as they are nearer to the areas of ongoing star formation. In all, this points to a highly complicated star formation history of Taurus, having at least two successive epochs of star formation featuring multiple modes (clustered and distributed) of star formation simultaneously. This work is published in The Astronomical Journal, and you read more about the methods and conclusions here.

Stellar activity in the NIR Helium triplet at young ages

Over the last 5 years, the NIR Helium triplet absorption feature (~10830 angstrom) has emerged as an extremely important probe to detect exoplanet exospheres and atmospheric mass loss. The commissioning of multiple NIR precision spectrometers (such as HPF) have made it easier to observe the NIR Helium triplet and observe samples of planets to search for exospheres and measure mass loss across planetary and stellar properties, which will help elucidate the cause and timescale of atmospheric mass loss. To understand the timescale it is necessary to look for exospheres as a function of age, particularly at young ages.

However, the NIR Helium triplet, which is a chromospheric line, is sensitive to stellar activity. Since activity is higher at younger ages, potential contamination of exosphere observations from the host star activity itself is a greater issue for young exoplanets. The activity-driven behavior of the NIR Helium triplet at young ages is not well-studied though.

In recently published work, I used a large set of HPF data of a sample of young exoplanet host stars to analyze the NIR Helium triplet absorption as a function of age, activity, and time. We find that the NIR Helium triplet is indeed variable from stellar activity, with increased variability at younger ages and the fastest rotation periods. The plot to the left shows the intrinsic stellar Helium triplet absorption variability vs. age, highlighting a precipitous decrease from high variability at the youngest ages. We also use the absorption strength to study the structure of young chromospheres and reinforce previously published conclusions that the NIR Helium transition in active chromospheres is driven by collisional excitation, implying that these active chromospheres are denser than older, quieter counterparts. Stellar activity can definitely affect and confuse exosphere observations, although for stars with ages above 200-300 Myr it shouldn’t totally prevent the detection of exospheres.

The main takeaway is just to be careful – while stellar activity isn’t a death knell for finding young exospheres, we just need to carefully considering transit timing, other activity indicators, etc. when interpreting exosphere observations. Take a look here for the arXiv posting of this paper to read more!

Outer architectures of young planetary systems

I am also using the HPF data featured in the Helium triplet project to search for outer giant planets in these systems with known inner transiting planets using HPF precision RVs.

Mapping the outer orbital architectures of these systems is a crucial constraint on the formation pathways of planetary systems, including the mechanisms behind orbital migration. The connection between inner and outer planets as a function of age, particularly in the first billion years when systems are most rapidly evolving, could elucidate the role of planet-planet scattering in the dynamical history of planetary systems. Finding young planets is difficult due to their intrinsic stellar activity-driven noise and challenges in measuring stellar ages. However, K2 and TESS have found dozens of young transiting planets using their high precision photometry, and leveraging membership in young clusters and associations to have a good grasp of the system’s age.

These systems are ideal targets to search for outer giant planets, but the activity-driven RV noise makes it challenging to fish planetary signals out of RV data. One way is by starspots, which will introduce temporally coherent RV jitter as the star rotates and the spots come in and out of view. This is illustrated in the animation on the right. One way to mitigate this issue is to observe in the infrared, where star spot contrast decreases and thus the effect of RV jitter is diminished. HPF is an ideal instrument to tackle this, with its highly stable instrumentation, NIR bandpass, and large amount of glass feeding it (the 10-m HET at McDonald Observatory).

My survey for outer giant planets is still ongoing and the full data set has not been analyzed in depth. There is a preliminary set of results for this survey in the third chapter of my dissertation (although there is emphasis on the word preliminary). We find some evidence for long-term trends in a handful of the systems, but the sparse cadence of the long-term RV monitoring makes the solid detection of periodic signals difficult. These data are also useful for understanding NIR RV jitter and its connection to other spectroscopic activity indicators, which is still just beginning to be explored with a significant sample of data.

Other assorted projects

Searching for new young stellar groups

Like I said above, Gaia provides an unprecedented look into stellar populations. This doesn’t just apply to groups of stars already established in the literature. The precision astrometry can be used to look for groups of stars not previously known by finding stars with similar 3D positions and on-sky motions. However, many stars in Gaia are missing radial velocity (particularly to sub-km/s precision) and there is no youth indicator information beyond Gaia photometry-based isochronal ages.

Those last two pieces of info can be added with high resolution spectroscopy, to measure radial velocities and traditional spectroscopic youth indicators like H-alpha and lithium abundance. I have done significant observing using the Tull coudé optical echelle spectrograph at McDonald Observatory to look at candidate members of young stellar groups, both known and unknown. For example, I have looked for new members of the distributed/older population of Taurus and also looked for the host stellar populations of young transiting planet host stars found with K2 and TESS. A poster with preliminary results from my survey for new Taurus members can be found here.

As a part of this effort, I wrote a pipeline for the Tull spectrograph to reduce its data and perform simple analysis, including measuring radial velocities and Li equivalent widths. I write more about this pipeline on my Software page.

Panchromatic RV activity signals in M-dwarfs

I have a collaboration with JPL to combine precision RVs from multiple instruments across wavelength to study the chromatic behavior of stellar activity-driven RV noise. We targeted active M-dwarfs with known rotation periods and activity signals, and observed using the APF in the visible and HPF in the NIR. We also obtained some observations with PARVI, which is further in the NIR than HPF. With high cadence, simultaneous RV time series from the APF and HPF we can analyzie the chromatic and temporal behavior of the activity signals. This is important, as knowing the timescales of activity and the use of multi-wavelength RVs are crucial to best plan and analyze extreme precision observations.

This work is ongoing, and you can see a poster with preliminary results I made for the Extreme Precision Radial Velocity 5 conference here.

Lithium abundances in star clusters across time

As an undergrad at SUNY Geneseo, I worked with Dr. Aaron Steinhauer on a variety of projects studying the lithium abundances of open and globular star clusters. Lithium is a sensitive and important tracer of chemical evolution in stars, where it can be produced and destroyed easily. Lithium depletes over time because it burns at relatively low temperatures, which makes it a fairly robust youth indicator. Lithium can also be created in the interiors of stars, although it often is immediately destroyed again. However, there are non-standard processes that could bring fresh Li to the stellar surface, which can then be observed and used to test models of the stellar interior. I worked on projects to map the Li abundances of both main sequence and red giant stars in multiple clusters, including open and globular clusters.